Every summer growing up I attended Vacation Bible School at our Presbyterian church in downtown Denver. We would do crafts, sing songs, memorize scripture verses about God’s love, and try to cream each other in games of dodge ball in the church basement.

Every summer growing up I attended Vacation Bible School at our Presbyterian church in downtown Denver. We would do crafts, sing songs, memorize scripture verses about God’s love, and try to cream each other in games of dodge ball in the church basement.

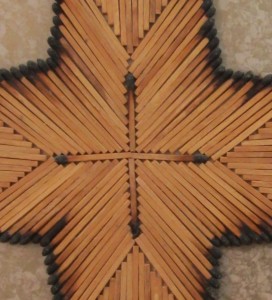

One summer one of our craft projects was to make a cross out of matches. We took partially burned matches and pasted them onto a cross-shaped piece of cardboard. Then our teacher had us glue the cardboard cross to a piece of contact-paper-covered plywood and told us to find an appropriate scripture passage to write on it.

I loved doing crafts, and this project was right up my alley. Painstakingly, I pasted my matches onto the cardboard, lining them up neatly, then glued the cross onto the backing. Then I thumbed through my Bible to find just the right scripture verse.

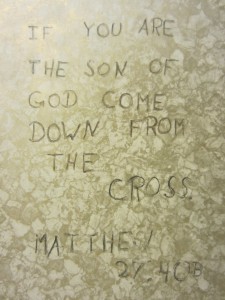

I was excited when I landed on the perfect verse. I carefully wrote it out, and proudly took my project to my teacher to show her.

As soon as she looked at it I could tell by her expression that I had done something wrong. She didn’t say what it was, but there seemed to be a problem with the verse I had chosen: “If you are the Son of God, come down from the cross.”My mother later asked me why I had chosen that verse. I gave her a simple answer, “Because it had the word “cross” in it.” What I didn’t say, since by now I knew I was treading on sensitive ground, was that telling Jesus to come down from the cross seemed like a no-brainer to me, and I didn’t understand why the adults were so uptight about it. He was the Son of God after all, so why wouldn’t he?

That was the first time I understood that when it came to Jesus there were certain beliefs you weren’t supposed to cross, so to speak.

As I got older, of course, I found out that the whole point of the crucifixion was that Jesus didn’t come down from the cross. It was a dramatic, though tragic, demonstration of divine love for a sinful humanity.

What Was This Cross?

But what was this cross he didn’t come down from?

When you strip away all the centuries of theology about the cross, what you come upon is a brutal torture tool used by the Roman Empire to terrorize the inhabitants of the lands they occupied. It was quite ingenious because, unlike most torture techniques of our day which take place under the cloak of secrecy, crucifixion was blatantly public. People deemed enemies of the state were crucified on the top of hillsides so that everyone could witness the slow, agonizing death it inflicted. The cross, then, was both a tool and a symbol of imperial power.

Empire, as we all know, is a political and economic system that conquers and exploits others in order to amass power and wealth. As such, it is an extreme enactment of what I often refer to as ego consciousness, the consciousness that perceives oneself (or one’s nation) to be a separate entity: separate from others, from Earth, from the Source of Being. Ego/Empire consciousness claims that by harming another, I gain.

Environmental devastation, poverty of the masses coupled with extreme wealth for the few, the pouring of resources into all manner of weaponry tell the story of the ego dream in graphic detail.

Jesus, however, embodied and enacted a very different consciousness that might be called divine consciousness: the knowing that Oneness (Love) is the only Reality. This consciousness sees that none of us is more special or more worthy than any other, power has nothing to do with domination, material wealth is meaningless, and death doesn’t truly exist.

Coming Down From the Cross

Because Jesus had awakened from the ego’s dream of separateness, he was not intimidated by empire’s so-called power, nor did his mind abide in the emperor’s reality. In every way that mattered, he had come down from the cross, and even though the empire could kill his temporal body, it was powerless to annihilate the God-consciousness he knew himself to be one with. In other words, the empire’s cross, which was never anything but a tool in a dream, was and always had been empty.

Of course, it wasn’t long before the followers of Jesus, awed as they were by their experience of his enduring presence with them, ascribed to him specialness, setting him apart from everybody else as the one and only Son of God. Ironically, the very things ego holds dear–separateness and specialness–came to be the defining attributes ascribed to Jesus, and the cross, empty and devoid of power in and of itself, was soon elevated to a mythic and divine purpose.

And yet, given that Oneness is the nature of Reality, we are all part of that Reality, no less than Jesus was. We are all equally “Sons and Daughters of God,” even though in our dream state we are unaware of it.

But when we do become aware of it, when we realize that that we are one with the Ultimate, we know that nothing–including the worst that the empire dream can conjure–can separate us from a Love that is indivisible.

In the light of that Love we can see that the dream of separateness that inflicts such suffering and makes us feel so vulnerable and alone, is a simply a story, nothing but an empty cross that we, that our world, can come down from.

Thank you.

You’re welcome, and thank *you*. Easter blessings to you and yours!

Dear Patricia, This is am amazing piece. I think you capture something so profound and true about the nature of all our faiths, the core message and the distortions that prevail. I sent it to several people who all shared my response. Thank you! To be continued. Sheila

Thanks, Sheila, and I look forward to the “to be continued” part. I would love to have a conversation with you about the core message and common distortions of our faiths. Who knows? Maybe we could even turn it into a blog post? 🙂

Thanks also for sharing the piece with others. I appreciate it.

Peace,

Patricia