Whether I was weeping outwardly I don’t recall. What I do know is that inwardly I was — from gratitude and a deep sense of relief for what the lump of clay in my hands was revealing to me.

I was at a workshop led by theologian Walter Wink and his wife June Keener-Wink, a potter. We had just been studying a biblical story about Jesus healing a paralytic whose friends had hauled him up onto the roof of a house, dug through it, and lowered their friend down on his mat to get him near Jesus, who was teaching in a crowded room below.

After we studied the text, we did a role play, and then June gave us each a lump of clay and instructed us to go find a quiet place and simply work the clay as we held the question: What in me is paralyzed?

As I sat kneading the clay, not trying to shape it into anything in particular, but just feeling its firm, earthy dampness, the answer to the question came suddenly, startling me with its uncompromising clarity: my creativity was paralyzed — and it longed to be set free.

Indulging Childish Ways

When I was a child I loved making things, drawing things, gluing things together. I drew horses, made little people out of cotton balls and felt, embroidered mountain sunsets on denim shirts, fashioned miniature houses from popsicle sticks.

But my creativity wasn’t limited to shaping physical objects. I invented secret codes to communicate with my friends, traveled (many times) to Mars and back on our swing set, and became a buffalo — became a buffalo — when my friends and I played our Wild West games out on the front lawn.

Somewhere along the way, though, I’d set aside those “childish ways.” In pursuit of more grown up, serious, intellectual interests my creative impulse and the joy that it brought me got tucked away in a trunk somewhere in the corner of my psyche, and, unbeknownst to me, had left a gaping hunger in my soul.

After the revelation that came to me during that workshop, I knew I wanted to welcome creativity back into my life, but I didn’t know how.

Not long after, as “fate” would have it, while I was on vacation in New Mexico I happened upon Julia Cameron’s book The Artist’s Way. It was exactly the right book at exactly the right time. Immediately, I began using the tools she recommends — doing three pages of free-association writing each day (a.k.a. the morning pages) and going on weekly artist dates, and over the course of the next several weeks I did the exercises at the back of each chapter.

Soon I was making collages, writing music, and singing at a local restaurant. I started coming alive in ways I had been longing to without knowing I was longing to.

That was way back in 1995, and still I get up early each morning and over my first cup of coffee write my three morning pages.

The Practicing Creative

What I didn’t realize when that clay offered its insight to me was how much releasing my creativity would transform my spiritual life. In fact, I now have difficulty distinguishing between them, because when I give myself over to a creative act I feel myself to be in a deep conversation, a communion really, with things unseen.

What I didn’t realize when that clay offered its insight to me was how much releasing my creativity would transform my spiritual life. In fact, I now have difficulty distinguishing between them, because when I give myself over to a creative act I feel myself to be in a deep conversation, a communion really, with things unseen.

I stand on the boundary between what is and all that could be, that churning froth of potential yearning to find shape, find words, find melody, find a beautiful way into this world of heartache and promise.

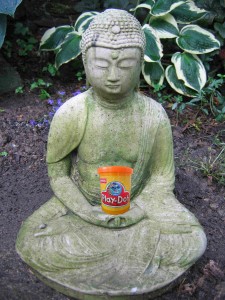

People sometimes talk about being a practicing Buddhist, or a practicing meditator, but I don’t know that many people think of themselves as practicing creatives. Yet in my experience creativity is a powerful, life-changing spiritual path.

I suppose it’s because the truly creative act cannot occur unless we give up what we think we know and enter what Buddhists call beginner’s mind. We must relinquish all of our preconceived ideas and our tightly controlled plans. We have to become a child again.

In his excellent book Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art, Stephen Nachmanovitch opens by writing about the Sanskrit word, lila, meaning play.

Richer than our word, it means divine play, the play of creation, destruction, and re-creation, the folding and unfolding of the cosmos. Lila, free and deep, is both the delight and enjoyment of this moment, and the play of God. It also means love.

Lila may be the simplest thing there is — spontaneous, childish, disarming. But as we grow and experience the complexities of life, it may also be the most difficult and hard-won achievement imaginable, and its coming to fruition is a kind of homecoming to our true selves. [Free Play, p. 1]

When we enter that state of being called creativity (which each of us, by nature of our nature, possesses), paradoxically we both lose ourselves and find ourselves. We lose ourselves in the sea of the infinite, and discover that the infinite is what we are.

Leave a Reply